4. Executing User Submitted Code

Our goal in creating Umbra was to allow users not only to code collaboratively, but also to run their shared code and receive evaluated results back quickly. Deciding where to execute this code, and determining how to execute it safely, were two of our major considerations.

4.1 Client Side or Server Side Execution?

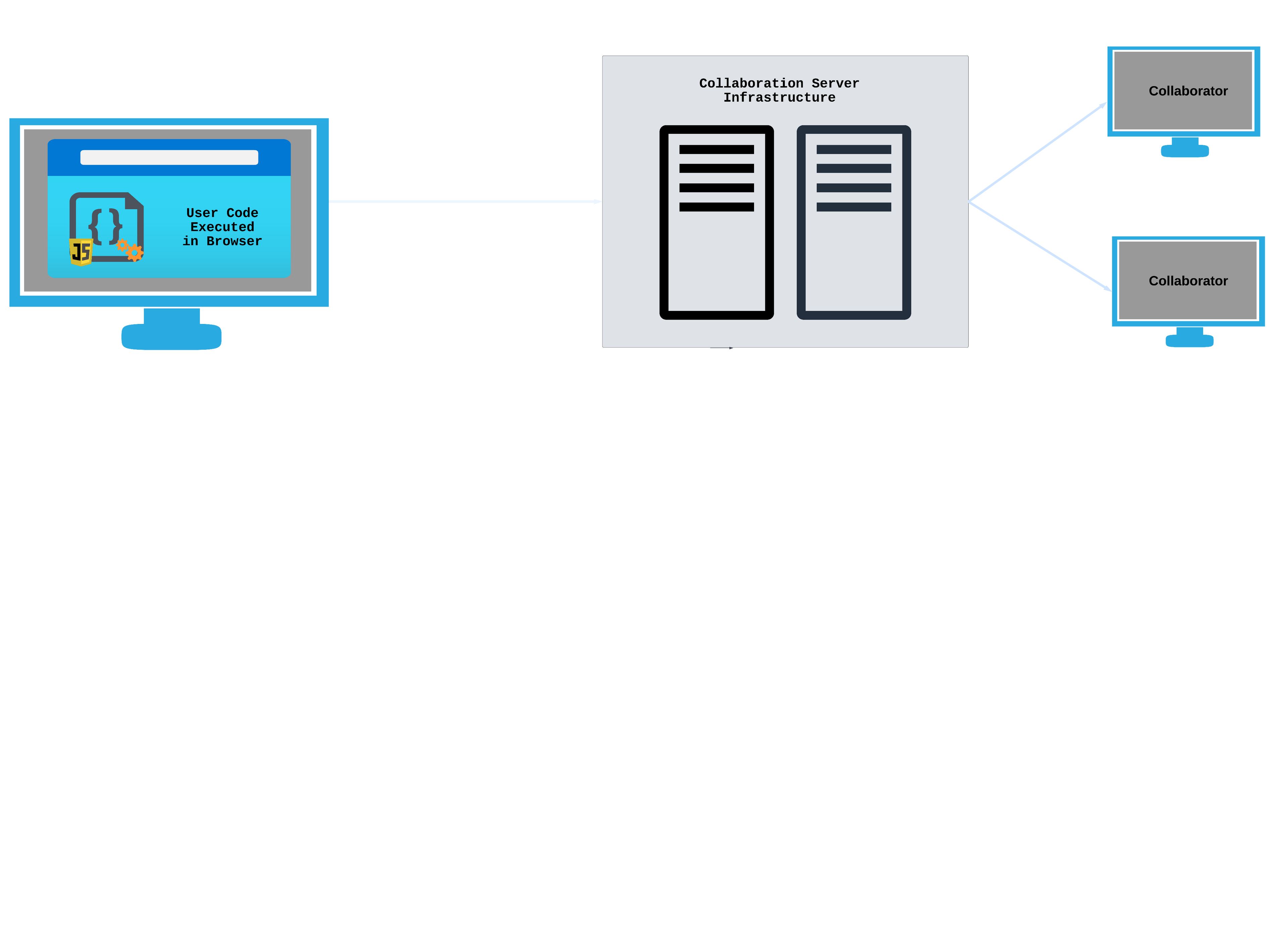

There are two broad options we considered when deciding where to evaluate the code submitted by users: in their own browser (client-side), or sent off somewhere else to be evaluated (server-side).

Either way, we knew we would need to sandbox the code execution environment. Sandboxing isolates external or untrusted code inside a restricted virtual environment, controlling its access to system resources. This prevents the code from accessing or even being aware of the underlying host system.

For instance, consider a JavaScript sandbox in a web browser

4.1.1 Client Side Evaluation

A web browser itself is already capable of evaluating more than just HTML and CSS. The ability of the browser to also evaluate JavaScript has been a cornerstone of the modern web, so why not leverage this existing architecture to evaluate user submitted JavaScript?

✅ No Network Round Trip for Code Evaluation

The user’s web browser is local to the machine they are using, so there would be no network trip to an external server to evaluate the code. This would reduce the latency experienced from the time of code submission to receipt of evaluation.

⚠ Web Browser is Partially Sandboxed

A web browser’s JavaScript runtime is sandboxed to a degree: the same-origin browser policy greatly restricts the ability for malicious code to do any damage beyond the user’s own machine. However, this sandboxing is not designed for executing arbitrary, potentially malicious code, and additional measures would be needed to ensure security. There are known methods to bypass the same-origin policy, and the web browser can’t limit the amount of CPU or memory a script uses to prevent resource depletion of the host system.

❌ Limited to Evaluating JavaScript/WASM

A web browser would only be able to evaluate JavaScript, and we were interested in allowing users to run code in other languages. It is possible to transpile code from other languages to JavaScript, or compile it down to Web Assembly, but this would involve extra processing steps and increase the users’ overall wait time.

❌ Reliant on Users’ Compute

Using client-side execution means putting more load on our users’ systems. It also reduces our ability to observe and control the execution performance; in the case that client side processing is slow, it will cause a lag for other connected users.

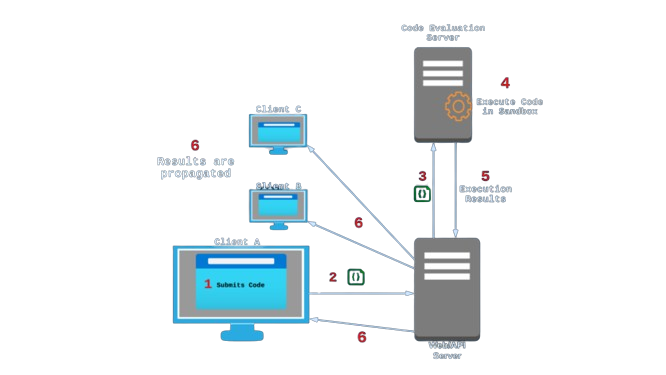

4.1.2 Server Side Evaluation

An alternative to executing code in the user’s browser is to evaluate the code on a remote server instead. This could be done on the same server hosting the Umbra web app, a separate server of our own set up specifically for evaluating users’ code, or a third party code evaluation service.

✅ Allows for Collaborating in Multiple Programming Languages

Having user-submitted code evaluated by a dedicated server process or third party API would allow users to collaborate in programming languages beyond JavaScript. We could support virtually any programming language by installing the correct compilers or interpreters on the remote machine.

✅ Controlled Code Evaluation Environment

Routing user submitted code to an external server would give us more authority over the execution environment. For example, we could set up logs to observe all execution requests; we could also exercise control with regards to security, including limits on memory and CPU usage.

❌ Possibly Greater Latency

When code has to travel to an external server for execution, it must take a network round-trip. For the user submitting the “run” request, this will result in a bit more latency in comparison to running the code on their own machine. (For other users, the difference should be negligible.)

❌ Potentially Dangerous Code

In the case of code being executed on the client machine, the code never has to leave the client’s machine. With server side evaluation, however, we open up the possibility for users to send destructive or malicious code to be executed on our servers, creating a significant security concern.

Ultimately, we decided on server-side execution. While either approach could work, having a server fully dedicated to properly sandboxing and executing code would help us create a better user experience by limiting the reach of destructive code, in addition to allowing us to support more programming languages.

4.2 Safely Executing Untrusted Code

The security issues involved with evaluating untrusted code are the focus of a vast amount of research and engineering. No method is ever 100% safe against attack, because attackers are always coming up with new ways to exploit previously unknown vulnerabilities in a system. For our purposes with Umbra, the focus was to reduce the space of vulnerability as much as possible, while weighing the tradeoffs of doing so.

4.2.1 What problems can arise from running untrusted code on a server?

Destructive code can originate from malicious actors, or from well-intentioned but inexperienced users. There are a few possible ways a bad actor can wreak havoc by exploiting a code execution environment that hasn’t been properly locked down:

- Depleting host system resources: Either on purpose or by accident, user code could deplete resources such as CPU cycles, RAM, hard drive space, and network bandwidth on the host machine. Examples include user-submitted attempts to mine cryptocurrency, or even just an accidental infinite loop.

- Allocating large amounts of memory (e.g. loading large asset files, or intentionally causing buffer overflows) can cause a host machine to slow down or crash.

- Data breaches: Without proper safeguards in place, it’s possible for an attacker to abuse elevated privileges on the underlying host to gain access to files and data that were not intended to be shared.

- Network integrity: Once a user gains access to a system via code, they are free to make requests to other nodes on that network. The malicious actor, appearing to be acting “from within”, could bypass any network security policies put in place to limit information access to the confines of that network.

In summary, allowing untrusted code to be executed on a machine means giving a stranger access to that machine. Proper safeguards need to be put in place to eliminate or minimize the ways in which the system could be compromised.

4.2.2 Sandboxing User Submitted Code

Despite the risks, executing untrusted code is a common occurrence. For example, it is a crucial business consideration for websites such as Coderpad, Leetcode, and CodeWars to protect their servers from potentially destructive user code. There are ways to minimize the potential for attack, and to ensure that the untrusted code can do zero or minimal damage to the underlying host system.

https://behradtaher.dev/2022/06/11/Sandboxing-Code-Execution/

One common method that we mentioned earlier is code sandboxing. There is more than one way to sandbox code, and different methods can keep the code more isolated than others, but all share the same goal of reducing the amount of harm untrusted code can do. Two approaches we considered using are virtual machines and containers.

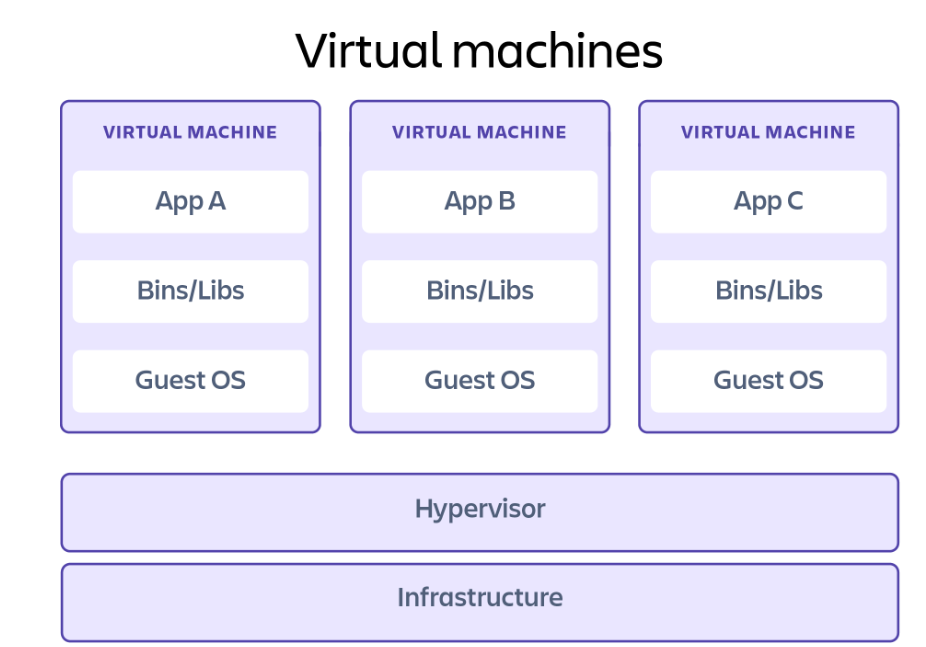

Virtual Machines

A virtual machine (VM) is essentially an entire computer system, with virtualized hardware and an operating system, that runs on top of the infrastructure of a host machine. Any code executed from within a VM is restricted to this environment. Without explicit access granted, it cannot access the underlying host. Any damage done is confined to this virtual machine, and handling the damage is simply a matter of deleting or resetting the VM.

Source: www.atlassian.com

Safeguards are still necessary to prevent access to network resources and the internet, but VMs alone are already a pretty secure way to isolate code. Exploits have been found where users can escape their VM sandbox and access the underlying host, but these exploits are generally found and patched very quickly.

Because a VM has to emulate both the hardware of a system and its OS, it does involve more overhead to load and run than some other sandboxing methods.

Containers

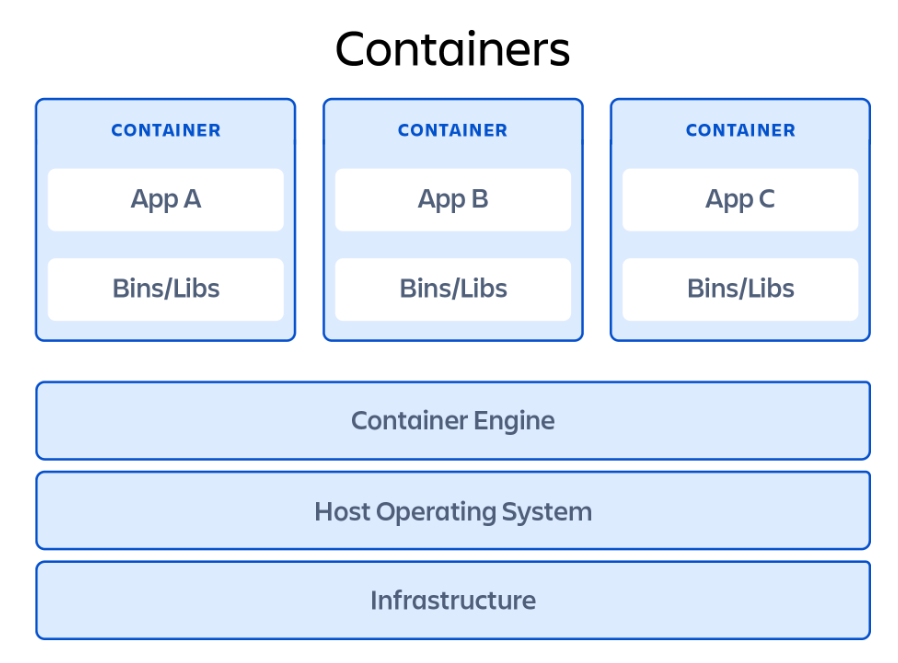

”Containerizing” untrusted code is a popular method of sandboxing, with Docker being a popular option. A container is similar to a virtual machine in that it sets up a virtualized environment for code execution. However, a container does not emulate hardware or an OS like a virtual machine does; instead, it shares the host operating system’s kernel.

Source: www.atlassian.com

This means there is less overhead work involved with a container, and it is generally lighter-weight and faster to start up than a VM. On the downside, containers aren’t as isolated as VMs because they share the OS kernel. Containers are also arguably easier to escape from than virtual machines, so there are generally additional safeguards to put in place.