2. Real-Time Collaboration

The phrase real time collaboration encompasses a broad set of scenarios in which users contribute mutually to some form of shared data store. In order to better illustrate what we set out to accomplish with Umbra, we will take a closer look at the terminology.

2.1 Definitions

In the context of the web, real-time refers to users’ experiences of latency: as long as the time delay between an event and a user’s perception of the event is small enough, the user will perceive the change as instantaneous. One example of real-time behavior on the web is that of data update feeds: users can view changes in metrics such as weather data, stock prices, or transport statuses in a way that seems to immediately reflect what’s going on in the physical world.

Collaboration, meanwhile, refers to multiple users engaging with the same medium. Generally speaking, collaboration over the web can happen in many ways, and it is not always synchronous. For example, multiple contributors to the same GitHub repository are engaged in collaboration with each other, but they are not collaborating in real-time. Instead, contributors handle conflicting changes by making pull requests and resolving conflicts manually.

2.2 The Technical Challenges of Real-Time Collaborative Editing

In a real-time collaborative editing application, the goal is to mimic the experience of working with others simultaneously—as if in the same physical room, or on the same computer. The main technical challenges of this goal involve resolving conflicting changes, broadcasting awareness data, and minimizing the latency of updates. Let’s take a closer look at what each of these mean:

- Conflict Resolution: What if two users happen to make changes at the same position in the document at the same time? Or what if one user temporarily loses network connection, and needs to receive batched updates upon reconnection? We need to ensure that in scenarios like these, conflicting updates will be settled in such a way that the users’ versions of the shared document are consistent with each other.

- Awareness: Each user should know which other users are “present”, what changes they are making, and when and where they are making those changes.

- Latency: Users need to receive automatic updates about the state of the shared document. Those updates should be received within a small enough window of time (about 200 milliseconds or less1) that they can continue their work seamlessly and trust that what they’re seeing is the most current document state available.

Two users working in the same document at the same time

2.3 Conflict Resolution

A collaborative editing application is a kind of distributed system, where there are several replicas of shared data: each user has access to their own copy of the shared document.

Since users are free to make changes to their copy at any time, temporary inconsistencies between these copies are inevitable. The keyword is temporary, though; in order to create a robust real-time collaborative application, we need a way to ensure that all user copies will eventually converge to the same state.

We came across two industry standards for implementing eventual consistency in collaborative editing: operational transformation (OT) and conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs). Both are used in industry-scale collaborative editing applications. However, we chose to proceed with CRDTs for a few key reasons:

- CRDTs do not require a central server to take on the burden of integrating every single document update. This allowed us to keep more options on the table when devising our system architecture.

- While horizontally scaling with OT is certainly possible, much of the literature we found suggested that it would be prohibitively complex to implement within our short development time frame.

Both approaches are the subject of a large amount of research; a complete review and comparison of them is beyond the scope of this case study, but we will provide a brief overview as context for the decisions we made.

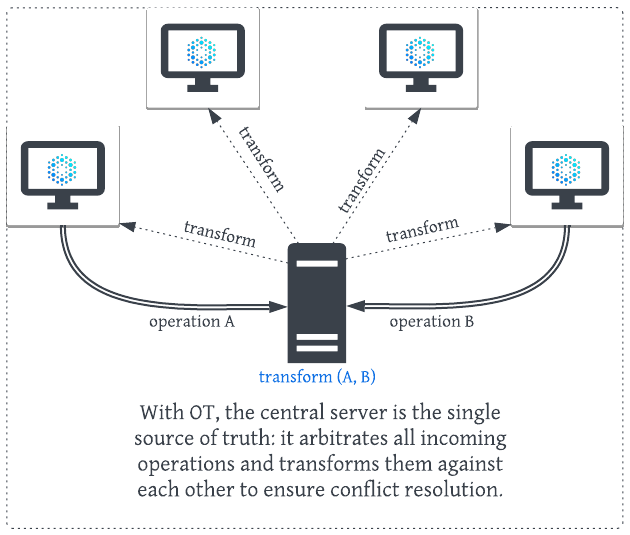

2.3.1 Operational Transformation

Operational transformation relies on a central server that functions as a moderator between all active clients. The server collects all changes to the document, applies them in an order of its choosing, and returns the results to the clients.

Essentially, there are three factors that govern the order in which user changes get applied in the OT model:

- the order of precedence assigned to each user by the central server;

- the position where the change occurred;

- the time at which the change occurred.

An important consideration with OT is that a central server is required to arbitrate changes, and this leads to a potential single point of failure. It may also lead to inconsistencies in the event of server downtime or network issues. On the other hand, a decentralized (CRDT-based) approach facilitates horizontal scalability, as the system can distribute the load across multiple replicas without a centralized bottleneck.

2.3.2 Conflict-free Replicated Data Type (CRDT)

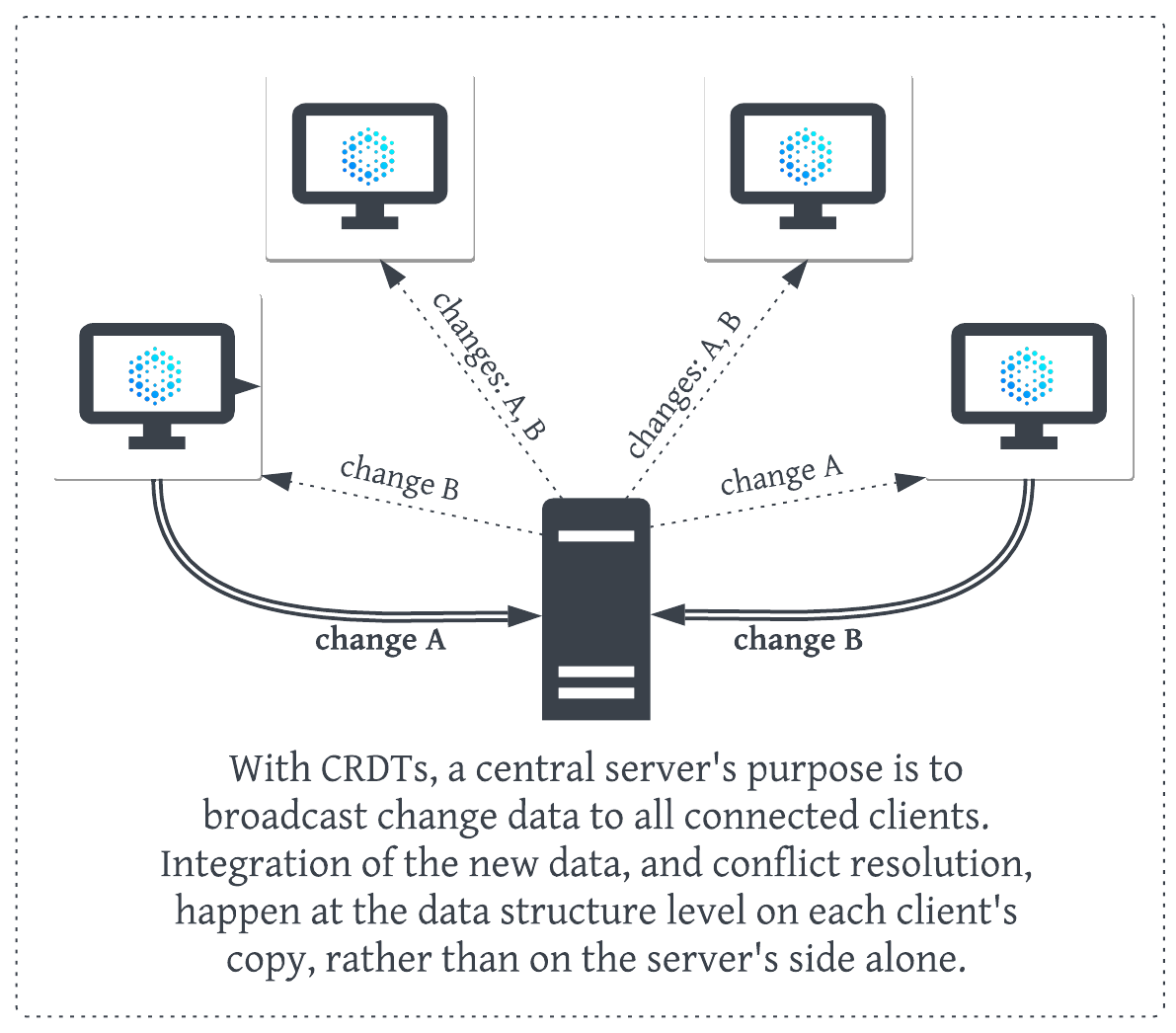

CRDTs are similar to OT in that they also provide a way for multi-source document changes to be applied sequentially. However, they differ in that conflict resolution is “baked in” to their structure, which eliminates the need for a centralized server. CRDTs accomplish this by adding some additional complexity to the underlying data structures that represent users’ changes.

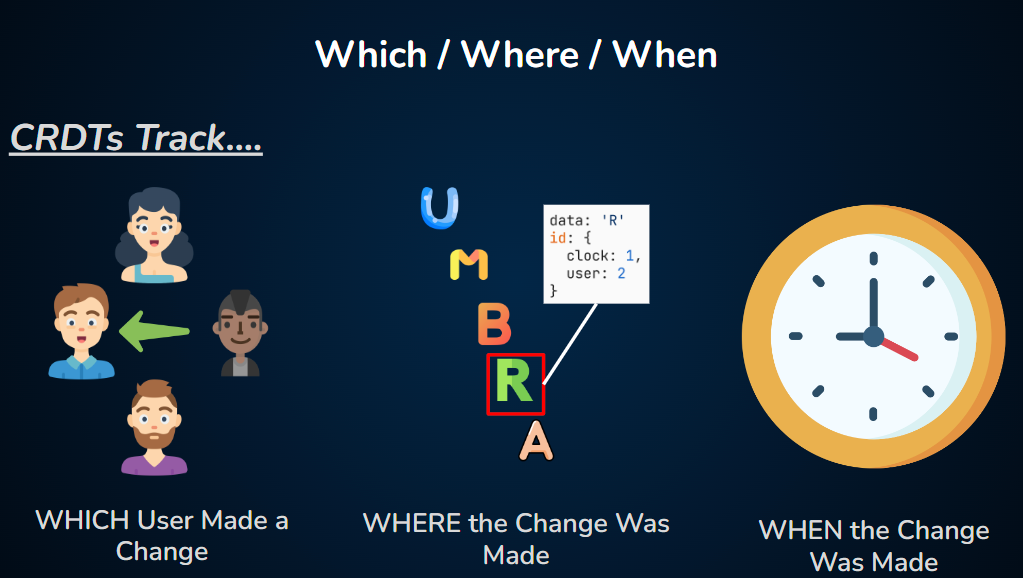

As with operational transformations, CRDTs track which user made a change, where in the document they made it, and when they made it. In addition, though, CRDTs assign each change a set of globally unique identifiers that further define its context and content.

This ensures that change events will be both commutative (successive changes will lead to the same result, regardless of the order in which they are applied) and idempotent (duplicate operations—such as two users trying to delete the same character—will not result in unwanted extra operations).

With CRDTs, all conflict resolution logic happens algorithmically, without a central arbitrator calling the shots.

The tradeoff—and one of the major criticisms of CRDTs—is that they involve significant memory and processing overhead. For example, each newly inserted character in a text document may be given its own unique ID. If ever a user deletes a character, it actually stays in memory; it’s just “marked” as deleted. Memory usage can accumulate significantly this way, particularly in large documents with frequent edits.

2.3.3 Yjs

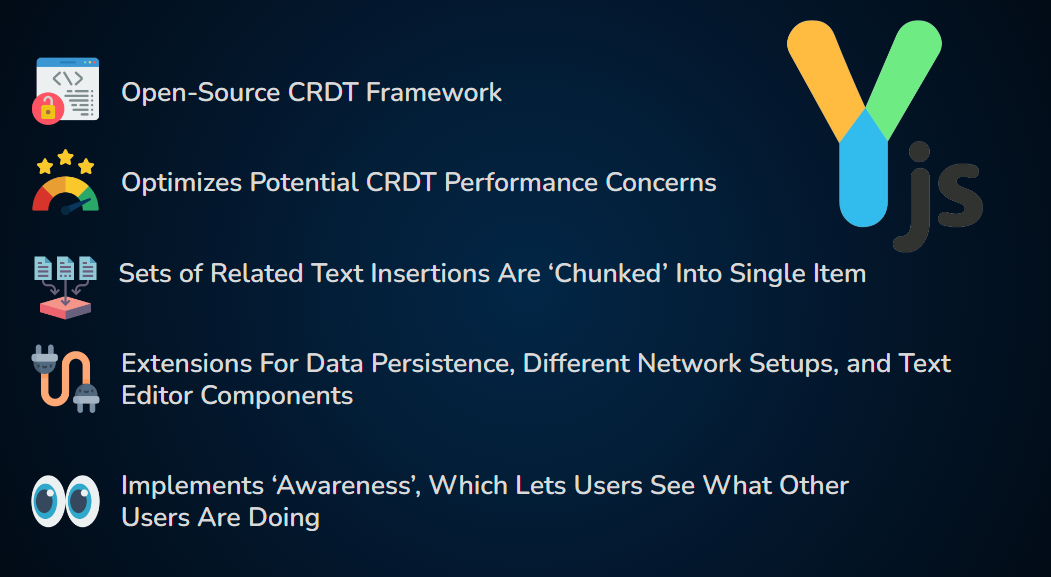

While the decentralized nature of CRDTs was appealing, we wanted a way to offset potential performance concerns associated with high memory and processing needs.

This led us to discover Yjs, an open-source CRDT framework that provides a degree of optimization under the hood: large sets of related text insertions are essentially “chunked” into a single aggregate change item. This leads to better performance with regards to operational cost and memory usage.

Yjs is not without its caveats: it is a relatively young technology, with several experimental elements. There are some outstanding improvements yet to be made; for example, it has been shown that with large numbers of clients (>10,000) on a given document, Yjs transactions can take up to 2 milliseconds each, which is quite slow. However, this was not a necessary consideration for Umbra’s use cases.

2.4 Awareness and Latency

Yjs was created specifically with real-time collaborative text editing applications in mind, and comes with a thriving ecosystem of extensions for several different network setups, data persistence options, and text editor components (see Section 3).

2.4.1 Performance Optimizations for CRDTs

In the prototypical CRDT model, each new character that a user types is assigned a unique ID and other metadata. In Yjs, multiple consecutive insertions (including copy-paste events) are merged into a single change item. This significantly reduces the number of new data objects created, and therefore lessens memory load.

2.4.2 CRDT-Based Awareness

Once there is a working setup for sharing and synchronizing CRDT-based shared document state, the stage is also set for managing awareness. In Yjs, awareness updates are also implemented as CRDTs under the hood, and are propagated between nodes in a similar way. The Yjs y-protocols module, which we will encounter in Section 3, offers protocols for syncing awareness information alongside document updates.

2.4.3 Latency

The performance optimizations that Yjs provides have a positive effect on latency. Additional factors influencing users’ perceived time lag are the choice of networking paradigm, and the physical distance between clients and servers.

In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at the technologies we chose for handling these factors. We will also dive further into the inner workings of Yjs, how we used it to implement collaborative editing, and what it took to integrate it into our application.

Footnotes

-

Robert Miller, “Response time in man-computer conversational transactions” AFIPS ‘68 (Fall, part I): Proceedings of the December 9-11, 1968, fall joint computer conference, part I — December 1968 Pages 267–277 ↩